“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” …. Bob Dylan

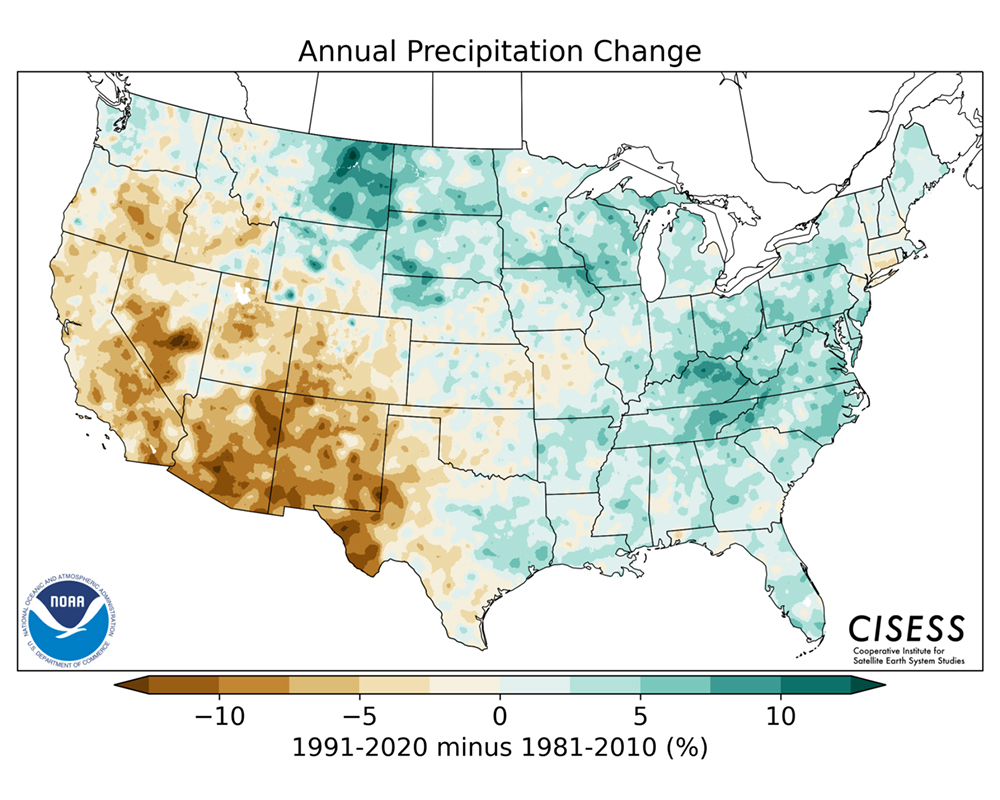

The last two decades have witnessed a significant shift in precipitation patterns across the Cumberland Plateau and middle Tennessee in general. Annual precipitation has continued to increase, a pattern seen in weather records throughout the 20th Century. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) used data from over 7300 weather stations across the country to chronicle precipitation changes from 1991 to 2020. Their results are illustrated in the map below and show a clear increase in precipitation in the middle Tennessee region and Cumberland Plateau.

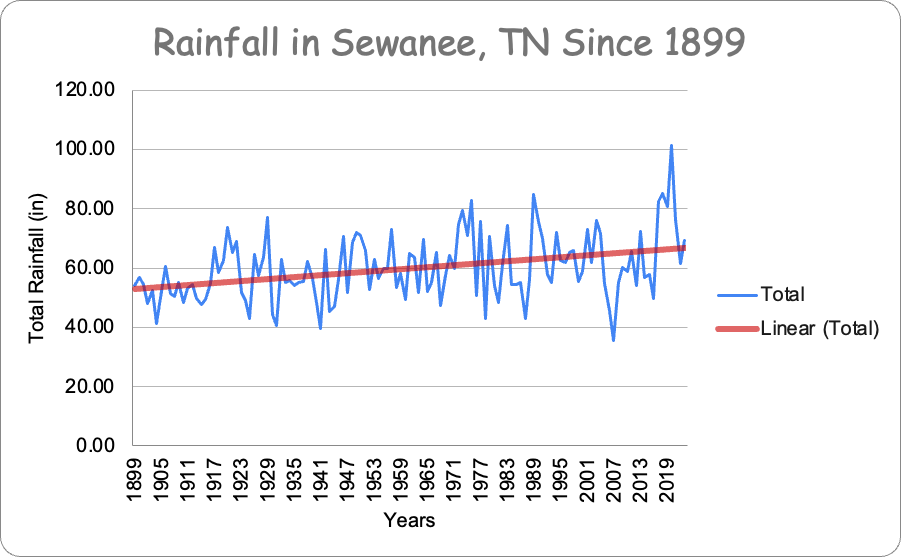

Weather records have been kept in Sewanee, Tennessee since 1899 and show an increase in precipitation through the 20th Century to the present (below).

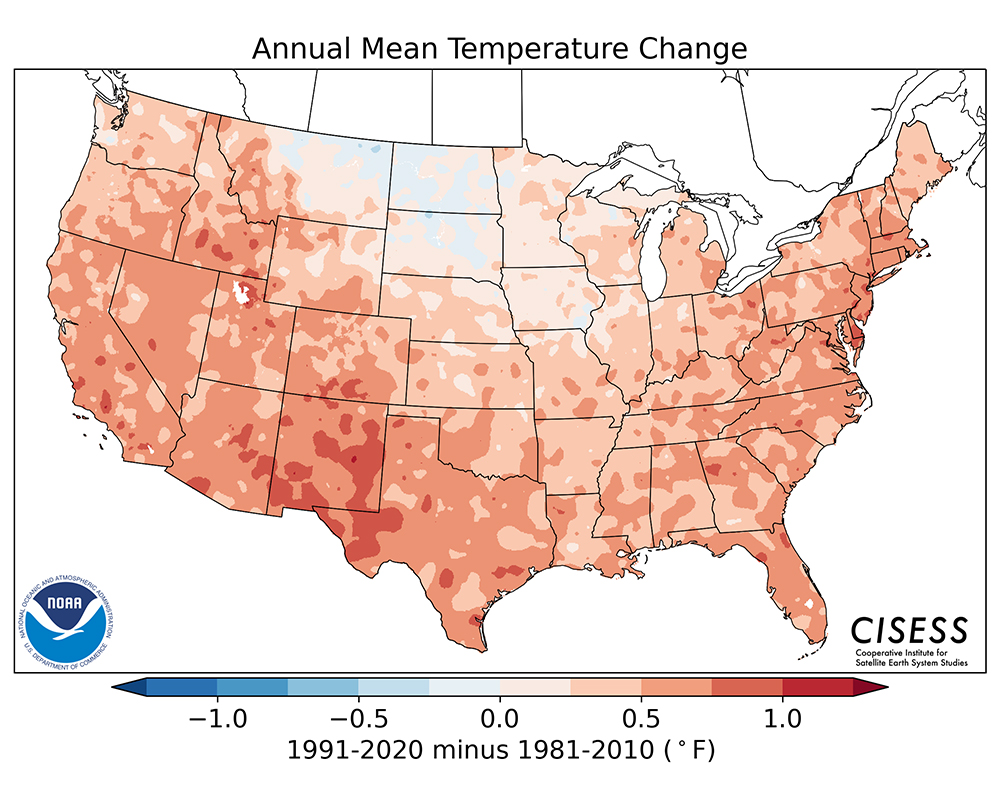

It is not just how much it rains annually that is important, but also how the precipitation falls across the year. Weather records show that heavy precipitation events, or downpours, have increased in frequency and intensity in the southeastern United States in the last seventy years. All Tennesseans remember the dreadful flooding in Waverly in 2021, when it rained 21 inches in one day and the resulting floods killed 20 people. In 2010 over 13 inches of rain hit Nashville in two days, resulting in extensive property damage from flooding of the Cumberland River and its tributaries. In neighboring Asheville, North Carolina up to 30 inches of rain caused extensive flood damage in 2024. This increase in downpours holds true for most of the rest of the US and is depicted in NOAA’s map below:

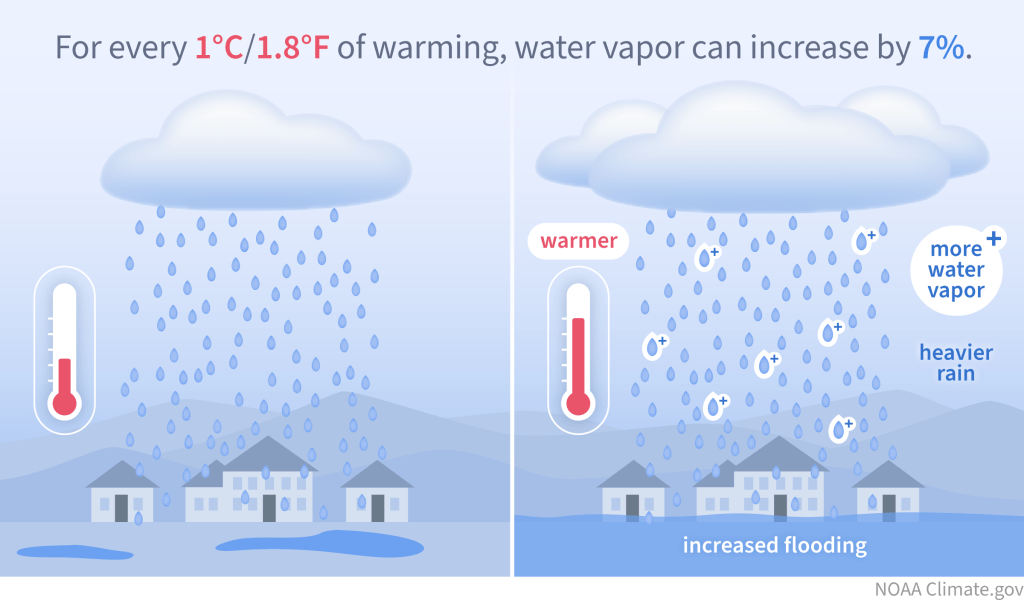

Why is our area getting more rain and why are there more and more heavy downpours? The reason is that the atmosphere over the southeastern US has warmed over the past 100+ years. One of the basic laws of atmospheric physics is that warmer air can hold more moisture than cold air. In fact, for every 1.8° F rise in temperature, the air can hold 7% more moisture.

Since warm air can hold more moisture, this means that the moisture may not be released for some time as rain, resulting in a drought. When the water is released it then often comes down as a downpour, resulting in flooding. Such a back and forth between droughts and downpours is often referred to as “weather whiplash.” Two of the most severe droughts of the last 125 years in Sewanee and the surrounding area have occurred in the last 20 years, specifically in 2007 and 2016. These droughts played havoc with water supply on the Cumberland Plateau, leading to very low reservoir levels, dry wells and infrastructure failures. During the 2007 drought the interstate rest areas in Monteagle (I-24) were closed due to lack of water. Sewanee’s primary drinking reservoir, the 130 million gallon (mg) Lake Jackson, was 34 feet below lake-full levels (the deepest point of the lake is 50 feet). In 2016 Lake Jackson dropped from 15 feet to 20 feet below lake-full levels from October 25th to November 26th.

Lake Jackson is part of Sewanee’s reservoir system, which is administered by the Sewanee Utility District (SUD). Its waters are pumped first into the smaller reservoir of Lake O’Donnell (80 mg), before water is treated at a filtration plant and sent on for public consumption. If the drought becomes severe enough and these lakes become critically low, then water can be pumped into Lake Jackson from nearby Lake Dimmick (230 mg).

Since all groundwater is fed by rain, exceptional droughts lead to declines in the water table and in the flow of springs. Tremlett Spring in Abbo’s Alley in Sewanee was flowing at near record low levels of 6264 gallons per day (gpd) in 2016, and 6171 gpd in 2007. For comparison, an average flow rate for the spring during non-drought years is around 12,000 gallons per day.

Although violent downpours may be the joy of water managers, since they tend to effectively fill reservoirs, they can of course result in greater rates of erosion (see post Stormwater on the Plateau) and flooding. In fact, the number of severe flooding events of the summer of 2025 across the US reflect the changing climatic conditions caused by global warming. The July 4 flooding of the Guadalupe River in Texas, the flooding of the Eno River in North Carolina near the same time, the generational flooding in Chicago and the fire-scar-enhanced flooding in Ruidoso, New Mexico are all a testament to our changing climate.