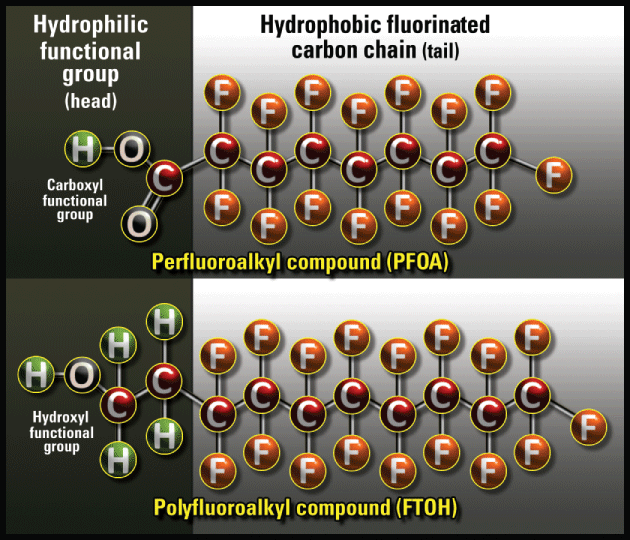

PFAS chemicals are a group of synthetic polymers (long chain molecules) that, once created, have a very long lifespan in the environment. This is why they are often referred to as “forever chemicals” or “persistent pollutants.” They are long-lived due to the fact that the bonds between the carbon and fluorine atoms in the structure are extremely strong. It takes a temperature of 1450°C to break these bonds – temperatures found in nature only in areas of volcanic activity. PFAS chemicals were first created in the 1930’s and there are now thousands of various forms of them that are used in a wide variety of applications including non-stick cookware (including Teflon), water and stain resistant coatings on clothing, carpets and furniture (including Scotchgard), food packaging and firefighting foam (Aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF). The unique structure of PFAS chemicals makes them ideal for these applications. As seen in the diagram below, the “tail” of the molecule is hydrophobic, meaning it repels water and oil, while the hydrophilic “head” of the molecule interacts with water. This means that PFAS compounds act as surfactants, reducing the surface tension between substances. When introduced into water, PFAS compounds therefore tend to congregate at the surface with tails held up out of the water and heads into the water. This is an important consideration for sampling for PFAS in water, as surface samples should provide the greatest concentration of chemicals and provide a “worst case” scenario for a particular water body.

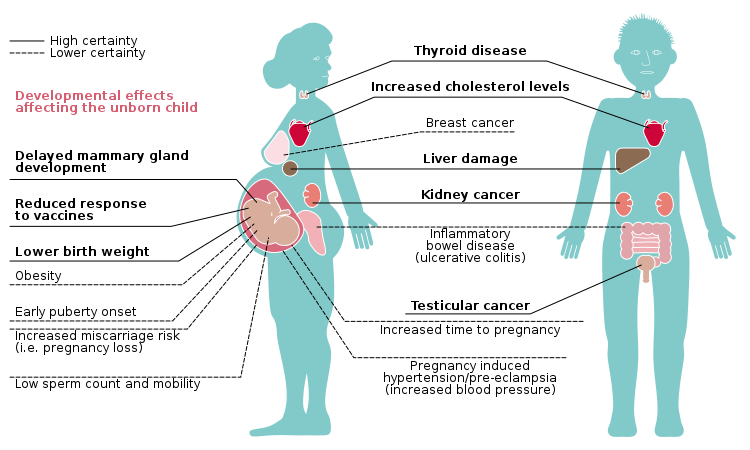

PFAS compounds are ubiquitous in the environment, having been found in living organisms, rivers, lakes, ponds, sediment and, most recently, in the snows of the Matterhorn and other European alpine peaks. They tend to be concentrated in areas of PFAS manufacturing, storage or disposal, or at airports and military air bases where firefighting foam containing AFFF has been used. PFAS compounds tend to bioaccumulate in the living tissues of organisms where they pose a variety of health concerns. Although these myriad potential effects are beyond the scope of this post, the diagram below provides a good summary of possible problems produced in the human body.

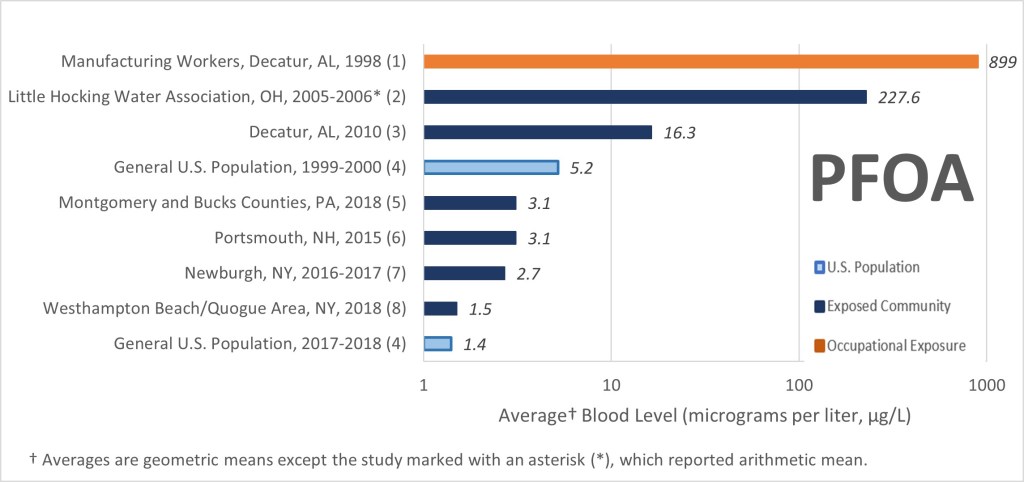

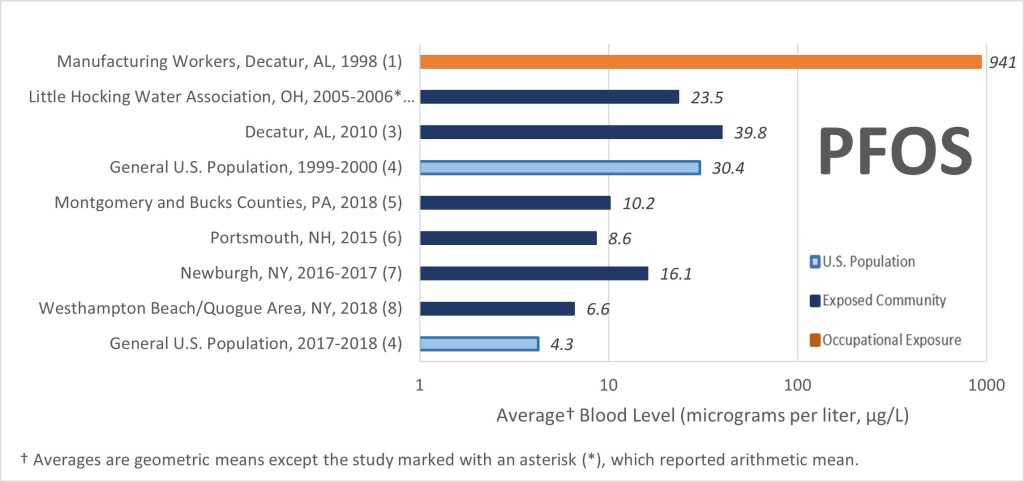

PFAS compounds are considered so toxic that even extremely small quantities in the environment are of concern. This is why they are measured in parts per trillion (ppt, or nanograms per liter, ng/l). One part per trillion is about the same as one drop of water in 20 olympic-size swimming pools. Studies have shown that most Americans have some amount of PFAS in their blood. The diagrams below show trends in blood contamination by two types of PFAS compounds, PFOA and PFOS, for three groups of people in the US over a period of 20 years. These groups include workers in PFAS manufacturing facilities, communities with PFAS-contaminated drinking water, and the general population. The reduction in concentrations over time is due to the gradual phase-out of these two particular chemicals since the early 2000’s. Of course, other PFAS compounds still in use likely don’t follow this trend.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has regulated five PFAS compounds in drinking water. Interestingly, the maximum contaminant levels permitted in drinking water for PFOA and PFOS are 4 ng/l, or 0.004 ug/l (ppb). Compare this number to the levels found in the blood of humans. The reason for the much higher PFAS and PFOS concentrations in blood compared to what is permitted in drinking water is the bioaccumulation effect of the chemicals and the years-long exposure of humans to the chemicals.

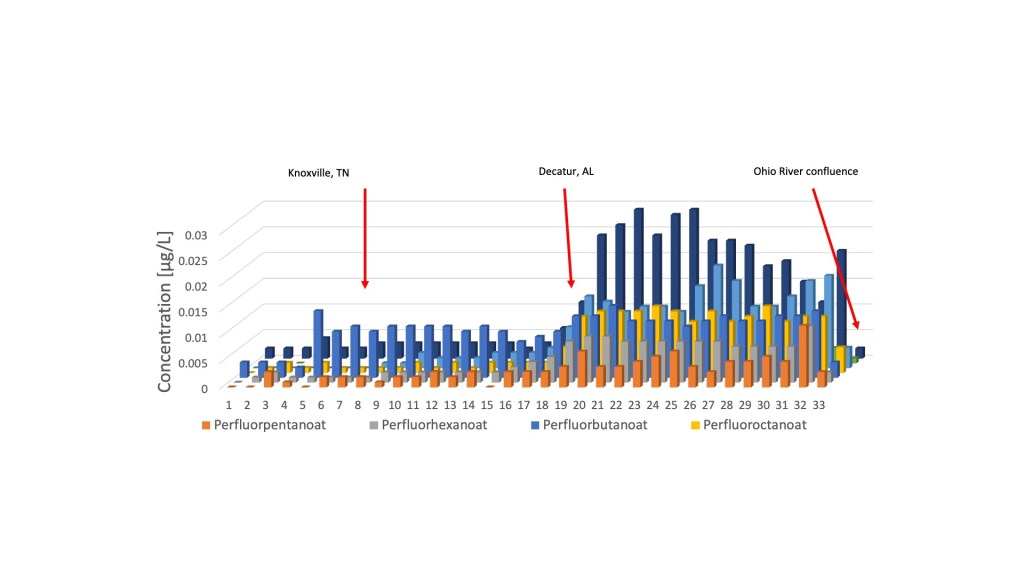

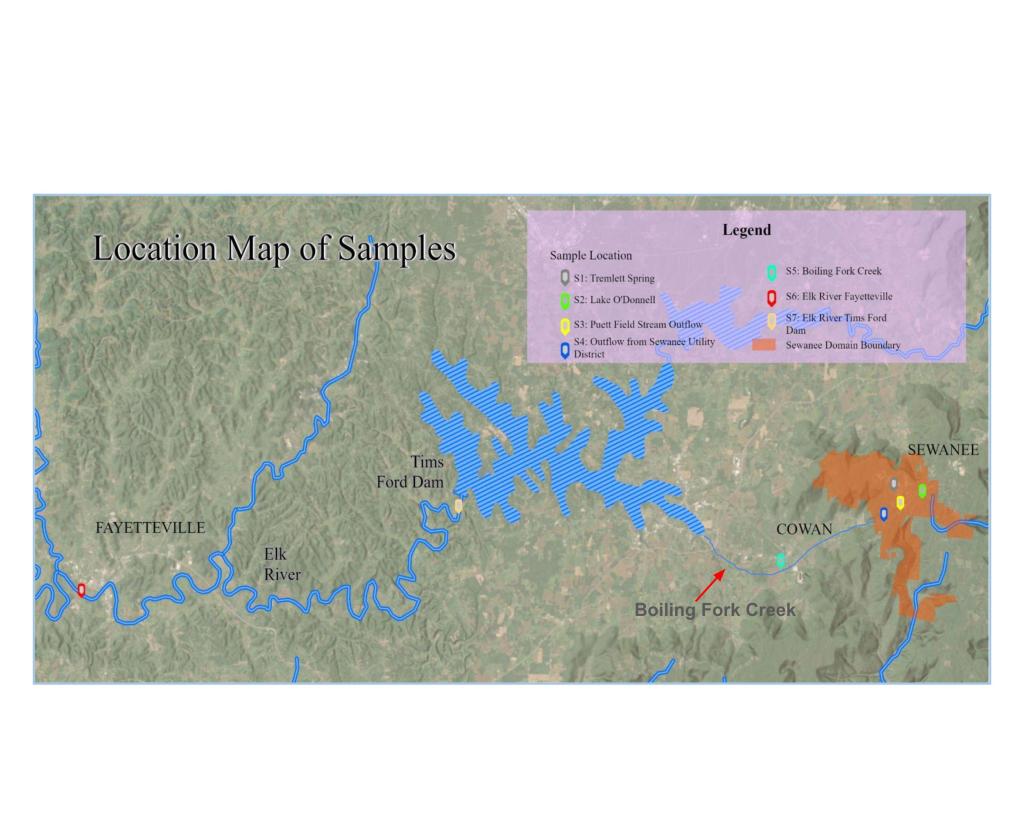

PFAS chemicals have also been found in the Tennessee River watershed and in the Tennessee River itself. I conducted studies of PFAS concentrations in a tributary of the Tennessee River (Boiling Fork Creek/Elk River) in 2025 and along the entire length of the Tennessee River in 2017 as part of the Tenneswim Project. These studies provide an interesting chronicle of PFAS contamination from the rooftop of the Tennessee River watershed through the Tennessee River all the way to its confluence with the Ohio River in Paducah, Kentucky. The tributary sampled was the Boiling Fork Creek, which begins atop the plateau in the town of Sewanee, Tennessee and flows southwest where it enters the 195 -mile long Elk River, which in turn winds its way southwestward to meet the Tennessee River in Alabama. Samples were analyzed for up to 40 different PFAS chemicals in stream water, a lake, a spring, and a stream with treated municipal sewage effluent (see the map with sample locations below). All samples contained some number of PFAS compounds, with select compounds show in the table below. With one exception, the values all along the Boiling Fork and Elk Rivers were below 3.1 ppt and did not show an increase downstream as one might expect. The lone high concentration of 6.8 ppt came from stream water emanating from an artificial turf athletic field. Plastic grass blades from such fields are known to be made with PFAS compounds. The Tennessee River contains similarly low levels of PFAS upstream from Knoxville, but then the levels increase near Knoxville. The Tennessee River PFAS chart shows a large increase in the compounds near Decatur, Alabama where the 3 M manufacturing plant had confessed to previously releasing PFAS into the Tennessee River. The levels remain elevated all the way downstream to Paducah, Kentucky.

Below are results from analyses of samples that correspond to sampling sites in headwaters of the Boiling Fork Creek, Boiling Fork Creek and the Elk River on the map above. All samples analyzed by a commercial lab using EPA method 1633.

- S1: Tremlett Springs PFOA 2.8 ppt

- S2: Lake O’Donnell

- PFPEA: 3.1 ppt

- S3: Puett Field (artificial turf athletic field) Stream Outflow

- PFHxS: 6.8 ppt

- S4: Outflow from Sewanee Utility District (municipal sewage treatment plant)

- PFOS: 2.0 ppt

- S5: Boiling Fork Creek

- PFOS: 1.2 ppt

- S6: Elk River Fayetteville, Tennessee

- PFOS: 0.57 ppt

- S7: Elk River Tims Ford Dam