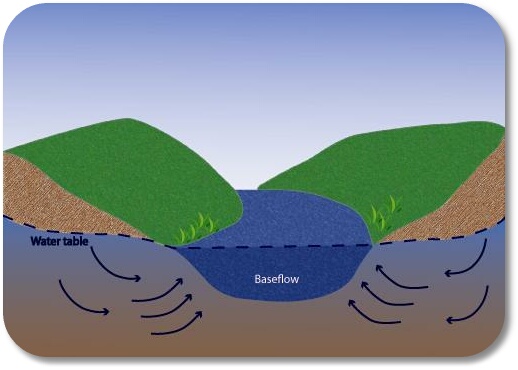

Streams and their tributaries are the most prominent features of any watershed in the eastern United States. When we walk or drive across a watershed, we correctly expect to encounter a stream at the lowest crease in the landscape. It’s relatively easy to understand that the stream has carved through the valley on its way downhill and out of the watershed. But how does the water get into the stream, or its tributaries, in the first place? When it rains only a small portion of water falls directly into the stream. During very heavy downpours we might see some water washing over land surfaces that usually don’t have any water on them. But why do streams still contain water days, weeks and months after the last rain? On the Cumberland Plateau and in many other regions of the Tennessee River Valley most of the water actually enters streams as baseflow. This is rainwater that has infiltrated the soil, moved its way down to the water table, and then moved laterally into the stream to sustain its flow long after the last rains have ceased. This process is invisible to us since it takes place within the ground and beneath the stream surface.

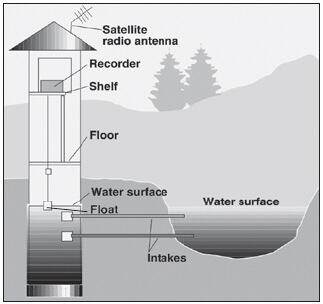

Baseflow enters the stream long after a rain event has taken place, but the amount of water added to the stream from the ground will diminish over time if not resupplied by rainfall. This is seen at the surface as a drop in stream level. How do we study and measure changing stream levels due to changes in baseflow? Most hydrologists pick a spot along a stream where the cross sectional area of the stream can be measured. Then they employ an electronic water level measuring device that is installed in a stilling well on the stream bank. The stilling well is connected to the stream and therefore shows the actual stream level at any time in a calm (“stilled”) environment.

Such an arrangement has been placed on the completely forested, 50-acre Split Creek watershed atop the Cumberland Plateau in Sewanee, Tennessee. Here a flume has been installed to collect all the stream water before it leaves the watershed on the edge of the plateau. A stilling well is attached to this flume and records water levels several times per minute.

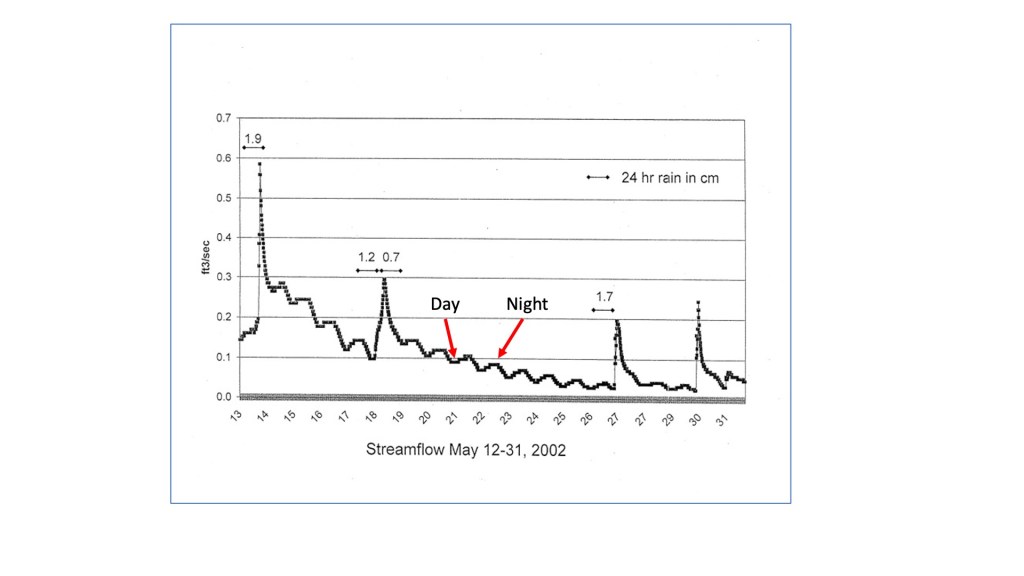

Data from this stilling well is plotted on a stream hydrograph and enables us to observe changes in stream level with changing rainfall and baseflow. The stream hydrograph below depicts 20 days of measurements taken in May of 2002 at Split Creek.

The Y-axis (vertical) shows stream flow in ft3/sec at the point where the stream leaves the watershed, but this can simply be viewed as stream level, where moving up on the axis indicates a higher level. The X-axis (horizontal) shows time in terms of days during May of 2002. So, what does this graph show us? The most obvious trend (reading from left to right) over the 20 days is the overall gradual drop in stream level. This is in spite of the four rain events which show up as brief, steep rises in stream level. The amount of precipitation in cm for each event is indicated by the bars above the spikes. One of the most interesting trends is shown by the daily, small bumps on the hydrograph. What would make the stream level rise and fall on such a daily (or diurnal) basis? This is the work of the deciduous forest which completely covers the watershed. During the growing season all plants from grasses and bushes near the forest floor right up to the tallest trees in the upper canopy take water up through their roots so that they can carry on the process of photosynthesis, whereby new biomass is created. This uptake of water by the forest is a daytime process, resulting in a temporary drop in the water table and in the amount of basefow entering into the stream. A kind of “inhalation” of water by the forest. On the hydrograph this shows up as one of the daily depressions (labeled “Day”) when the stream level is lowered. When the plants stop pumping water up during the night, the water table and baseflow rebound, leading to a “bump” on the hydrograph (labeled “Night”), indicating a rise in stream level. This diurnal spectacle represents the collective “breathing” of the forest. Where does all the water taken up by plants go? The vast majority leaves the plants during the sunlight hours as water vapor from small pores (stomata) on the undersides of leaves. This process is called transpiration.

Transpiration returns water to the atmosphere, where it condenses to form clouds, and ultimately rain.

For more on Split Creek Watershed, visit http://www.splitcreek.sewanee.edu.