An old, shallow well in Sewanee.

Before we successfully built the first modern reservoirs in the Sewanee area in the 1950’s, well water was an important component of our water supply along with the few perennial springs in the area. The first wells were hand-dug, extending down through the soil and then through as much of the weathered bedrock as the well diggers could manage. These old wells (like the one pictured above) typically ranged in depth from 20 to 35 ft. A rare glimpse into a well behind and old residence on University Ave. and in the woods on “Billy Goat Hill” in Sewanee reveal that the structures were rock-lined and between 3 and 4 feet in diameter (see photo below).

Interior of a long-abandoned, mostly infilled, rock-lined well in Sewanee. The rock lining presumably extended down through the soil until bedrock was reached.

The rock lining would have prevented collapse of soil into the well and presumably did not extend into the bedrock to any great distance. Upon completion, the well was capped with a lid and a pipe moved water from the well bottom to the surface via a hand-operated pump. These old wells were problematic for two main reasons. The first is that their shallow nature meant they would run dry when the water table dropped due to drought or seasonal decline during dry periods of the year (summer and fall). The second issue is that they were not sealed off (or cased-off in well driller speak) from the surface. That meant that surface water, along with any contaminants it carried, could easily infiltrate the well. During heavy rains one can sometimes hear water pouring from the surrounding soil down into these old wells. This was not a good arrangement if a privy or concentration of animals was near the well.

Today wells are drilled with much greater ease using compressed air drilling techniques, so that a well over 100 ft. deep, penetrating hard sandstone, can be completed in just a few hours.

A 100 ft.+ deep well being drilled on the campus of the University of the South in Sewanee.

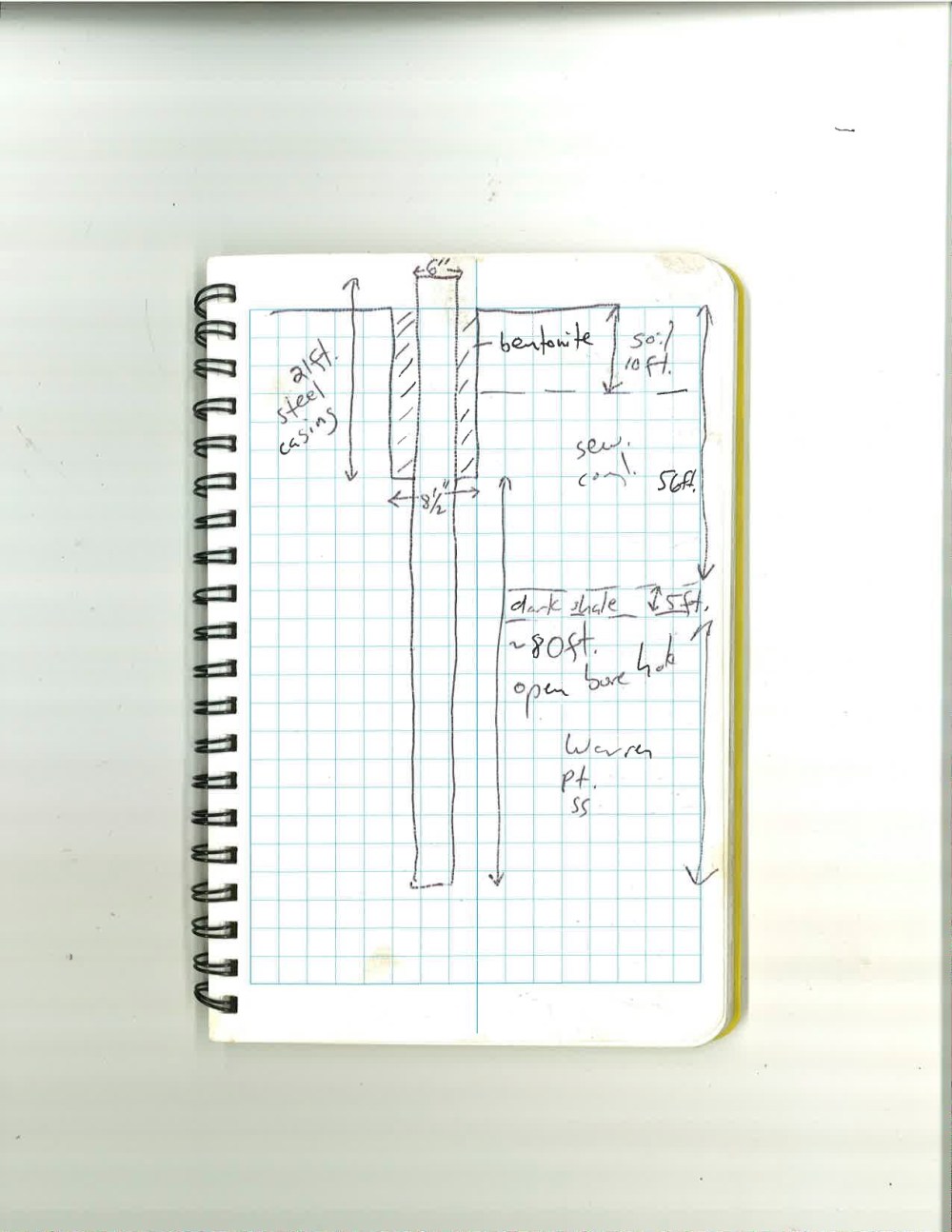

These wells are cased off for the first 21 ft., so that there is little chance of surface water entering the well. Below are field notes showing the construction of a modern well in Sewanee:

The field notes show that a 8.5 inch diameter hole is first drilled through the soil and then into the bedrock to a depth of 21 ft. Steel casing (a steel tube) of 7 inches diameter is then placed in the larger hole. The space around the outside of the steel casing is then filled with a bentonite slurry. Bentonite is a swelling clay and forms a tight, waterproof seal around the steel casing. Now a 6 inch diameter hole is drilled to the desired depth below the water table. In most cases the borehole is left unlined, with the firmness of the rock preventing the hole from collapsing.

Steel casing of a modern water well protruding from the ground.

Why then, with this efficient method of providing safe access to groundwater, have most people on the Plateau chosen to opt for reservoir water as their drinking water source? The answer lies with issues related to both water quantity and quality. A quick glance at the water well drilling records maintained by the state of Tennessee (or in conversations with well drillers) reveals that the average yield of wells on the Plateau is between 3 and 5 gallons per minute. This might prove satisfactory if one has the ability to store the well water in a large tank, but this does not suffice for a household pumping the water directly from the well into the house. The reason for these low yields is primarily due to the fact that the sandstones and shales of the upper Cumberland Plateau have relatively low permeability. Water travels through these layers mainly along fractures and one must be fortunate enough to have a well that intersects these fractures. Predicting where these fractures are found in the subsurface is not possible. Compare these yields to those from wells drilled in the valley surrounding the Plateau, where wells often produce from 80 to 100 gallons per minute. This increased production is due to the fact that valley wells are drilled into very permeable limestone that is honeycombed with caves and passageways filled with water. Drilling deeper on the Plateau down into the limestone will not increase yield, since caves and associated passageways do not extend beneath the sandstone cap of the Plateau.

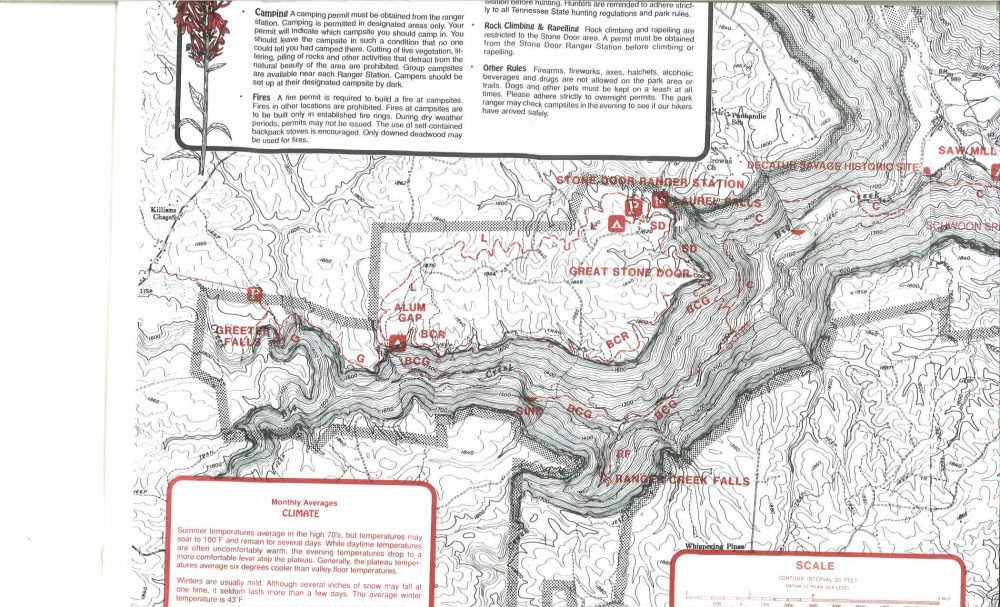

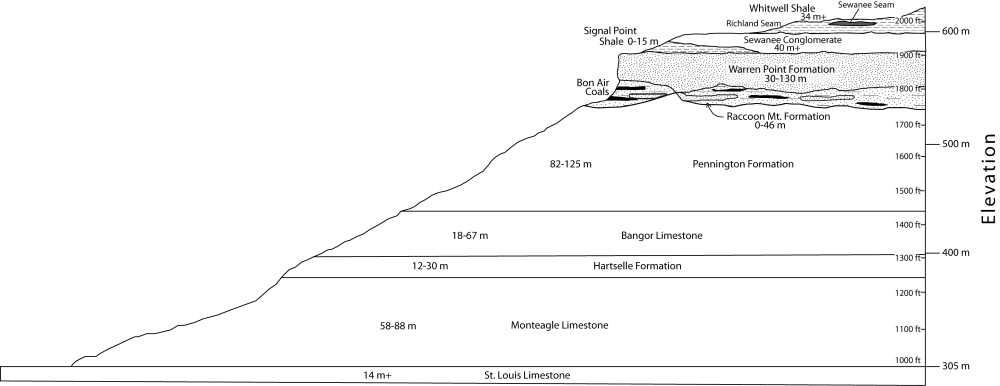

- Geologic cross section of the Cumberland Plateau near Sewanee. Rocks above the Raccoon Mountain Formation are relatively impermeable sandstones and shales. Rocks below this layer are chiefly limestones with good permeability given to them by caves and passageways only in areas not under the sandstone cap.

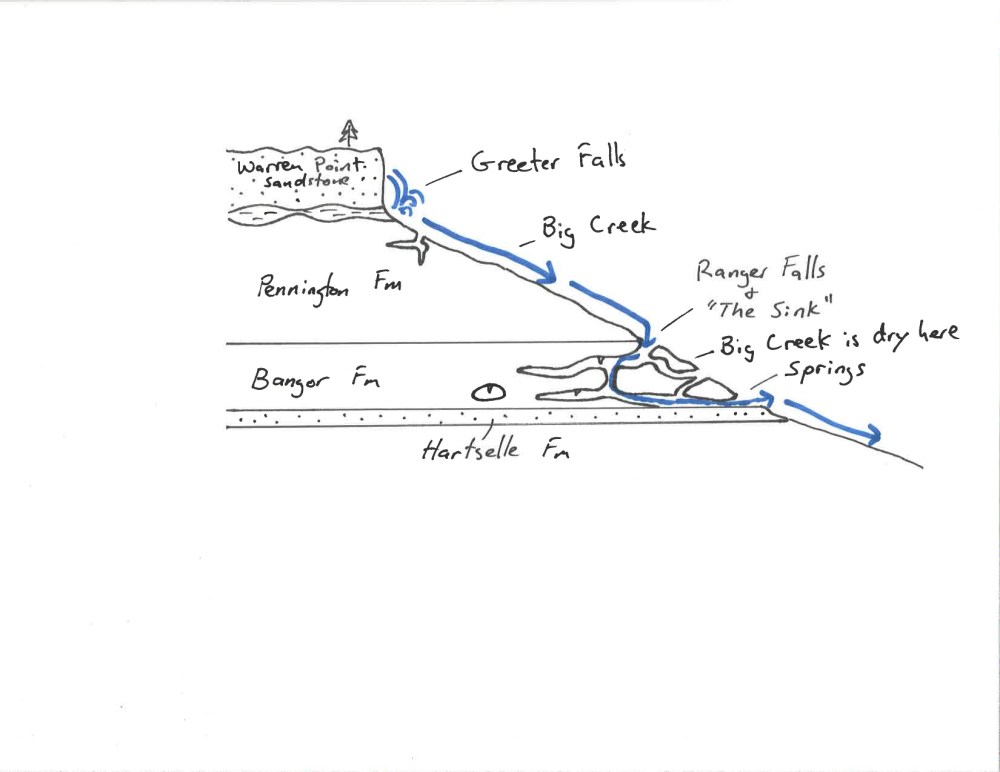

The second problem with well water on the Plateau has to do with reduced quality because of high levels of iron. Now, iron is not considered a primary contaminant in drinking water by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Rather, it is classified as a secondary, or nuisance contaminant, causing stains on bathroom fixtures, turning white laundry pink, and clogging water filters. The general rule of thumb is that the greater the depth from which water is drawn from a well, the higher the iron content will be. This is due to the fact that deeper groundwater contains less dissolved oxygen than shallow water. Dissolved oxygen makes the iron precipitate out of solution (turn solid) and settle out of the water. The same trend is seen in spring water. Shallow springs (like Tremlett Spring in Abbo’s Alley or Hat Rock Spring) are very low in iron. These springs emanate from the Sewanee Conglomerate (see cross section above), which sits on top of the Plateau in the Sewanee area. Deeper springs that emanate from the underlying Warren Point Sandstone have much higher levels of iron and have historically been called chalybeate.

A chalybeate (high iron) spring emanating from the Warren Point Sandstone in Sewanee. As the oxygen-depleted groundwater meets the air, the iron precipitates out as a solid.

The ultimate source of all the iron in the groundwater is from the weathering of iron-bearing minerals in the sandstone.

So, due to low yields and high iron, the vast majority of people on the Plateau have opted for reservoir water (if it was available to them) instead of well water.